'Of the over 300 sites I visited only seven had any type of memorial. Something about these lives not being recognised, even on the land itself, upset me most. As a nation, we weren't taking stock. We rarely, if ever, marked the ground.'

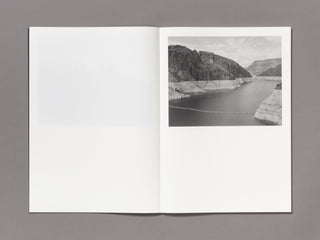

The black and white photographs in My America are of city parks, shopping malls, parking lots, mobile homes, empty fields, and roadside highways. By photographing these banal landscapes Matar declares that what happened at the locations matters and questions the link between landscape and memory.

'Can a photograph tell us anything about what has happened before the photographer arrives… even if not, I believe there is value in documenting the ground where violence has taken place... Perhaps a photograph can offer ways to remember acts of injustice that have been forgotten or never made transparent.'

Previously, Matar, an American living in London, spent years documenting sites of state sponsored violence in North Africa, Eastern and Southern Europe. In 2015 she turned her lens on her own country and began researching who, how, and where citizens were dying in police encounters in the US. She created detailed maps in her studio and compiled information about each victim who died in 2015 and 2016.

‘I wanted to address the issue of police

violence in a way that wasn’t just polemic.'

A small grant from the Ford Foundation enabled her to make six road trips over the next four years. She photographed in states with the highest numbers and/or highest rates per capita of lethal encounters—Texas, California, Oklahoma, and New Mexico—travelling alone on highways, back roads, and

city streets to reveal something beyond statistics. After Matar finished photographing, she spent two additional years researching the legal outcome of each case. The result is a book designed with respect to the victims but also rich with information about the structural reasons why these events continue to occur at such a high rate.

'In a world where millions of pictures are taken each day, I still believe photographs can contain meaning; they can become evidence of things not seen or heard... if, as I believe, to photograph is a desire to know something deeply and beyond the surface, I must be quiet to see. And attending to something says I acknowledge it matters.'